Authors: Tim Daubenschütz (OP EIP-4973), Raphael Roullet (Violet), Rahul Rumalla (Otterspace)

Last updated: 2022-06-27

Ever since Vitalik Buterin's first post on Soulbound tokens, Weyl, Ohlhaver and Buterin then followed up with a paper titled "Decentralized Society: Finding Web3's Soul." Subsequently, but also before, many efforts spawned to implement their proposed roadmap: Here are just some of the on-going ones: "Account-bound" (ABTs), "Soulbound" (SBTs), "non-transferrable" (NTTs), "name-bound" (NBTs), "non-tradable" tokens (NTTs) have been the focal point for discussion in the Ethereum community.

As the topic is rather fresh off the press and since not many people have had time to thoroughly think through some of the concepts proposed in Weyl et al.'s paper, we, the authors of the Account-bound tokens specification EIP-4973, have had to see several uninformed takes we'd like to address with this post conclusively.

Additionally, since we stray of the the beaten path to define a original financial primitive for EVM-chains, it's important that our work doesn't get conflated with all the existing efforts. So this post serves as a living knowledge base for all decisions made to develop EIP-4973 Account-bound tokens.

Below, segmented in sections, are the most common misconceptions about Account-bound tokens and how we think about them. And before we get into the meat, please let us prefix the article by stating that we, too, are "beginners" in this recently emergent field. But we're narrowly focused on delivering a standard, so we believe we have a position and voice worth hearing in the discussion.

We think a good primitive design intends to do one specific task in a precisely defined and highly reliable fashion - this is one of the first principle approaches we took with ABTs, i.e., how do we best bind tokens to accounts with consideration of consent and recoverability in mind.

But before we dive into the misconceptions, let's define what we mean by "Account-bound tokens/property".

To define where the terms "soulbound" and "account-bound" stem from, we have to go back to their invention, namely to when World of Warcraft's game designers intentionally took some items out of the world’s auction house market system to prevent them from having a publicly-discovered price and limit their accessibility.

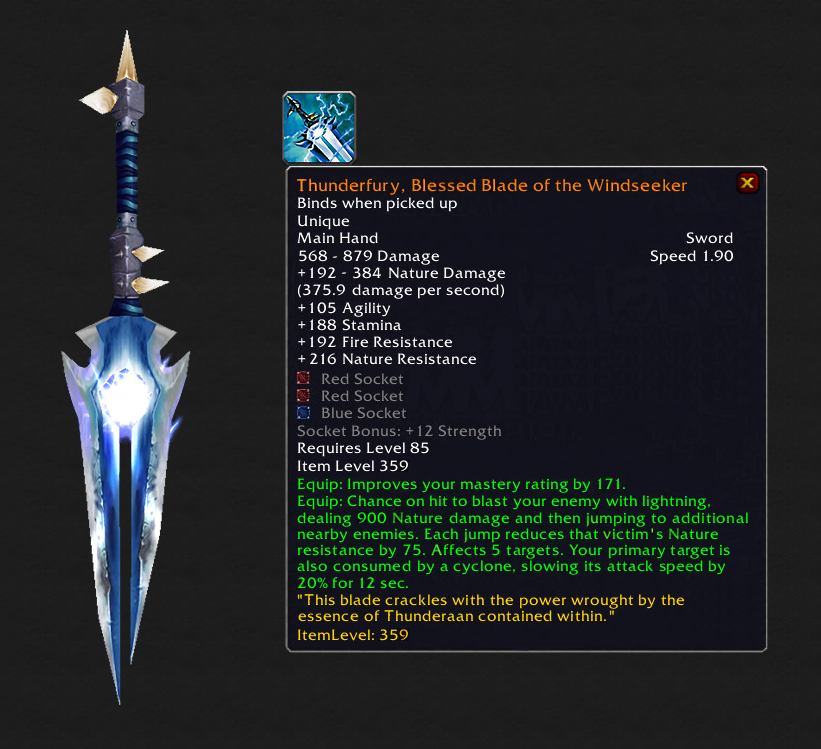

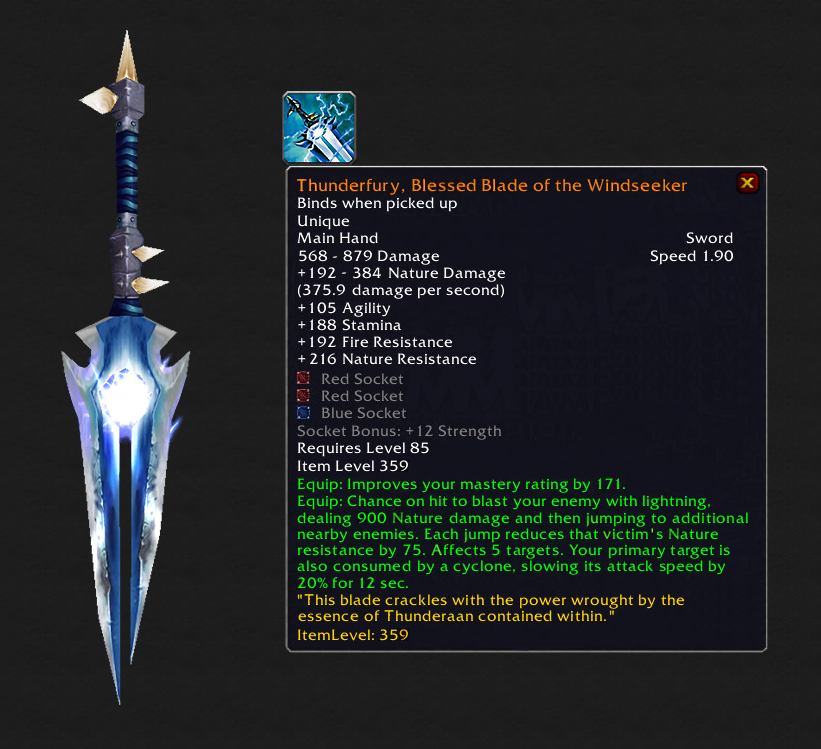

Vanilla WoW’s “Thunderfury, Blessed Blade of the Windseeker” was one such legendary item, and it required a forty-person raid, among other sub-tasks, to slay the firelord “Ragnaros” to gain the “Essence of the Firelord,” a material needed to craft the sword once.

Upon voluntary pickup, the sword permanently binds to a character’s “soul,” making it impossible to trade, sell or even swap it between a player’s characters.

In other words, “Thunderfury”’s price was the aggregate of all social costs related to completing the difficult quest line with friends and guild members. Other players spotting Thunderfuries could be sure their owner had slain “Ragnaros,” the blistering firelord.

World of Warcraft players could trash legendary and soulbound items like the Thunderfury to permanently remove them from their character.

The Ethereum community has expressed a need for non-transferrable, non-fungible, and socially-priced tokens similar to WoW’s soulbound items. Popular contracts implicitly implement account-bound interaction rights today.

So similar to "soulbound" swords in World of Warcraft, an account-bound token/property on Ethereum isn't sellable in any auction house. It cannot be transferred from one user's account to another and so it doesn't have a publicly-discoverable price.

Finally, EIP-4973 "Account-bound tokens" defines a canonical Solidity interface for e.g. token wallet implementers. A principled standardization helps interoperability and improves on-chain data indexing.

Now, below is a discussion of the most common misconceptions of Account-bound tokens.

I see many people excited about non trade-able "soul-bound" tokens. But it can happen that you need to change your address due to one of many reasons:

— Lefteris Karapetsas | Hiring for @rotkiapp (@LefterisJP) May 29, 2022

- Better security

- software to hardware wallet

- new key derivation algorithm

- Key compromised

- Lost key

What do you do?

The most common concern we've heard when introducing the concept of binding tokens to an account is that it discourages users from frequently rotating keys. However, given the standard's current state and that revocation or "revocation and re-assignment" are a possibility, the standard itself makes no normative statements about an ABT being permanently bound to an account - even in case of key loss.

Quite the opposite, while EIP-4973

ABTs do indeed not implement

EIP-721's transfer and

transferFrom functions, it's intentionally designed to leave the

responsibility of re-assignment and revocation up to the implementer, i.e., a

community, a protocol, a dApp, and not impose this as part of the primitive

itself.

But additionally, in the next paragraphs, we detail how Account-bound tokens can further encourage key rotation and even help improve the social recovery of wallets. It's because Account-bound tokens are really just the primitive to build social wallets and so we can frame EIP-4973 as a new token standard that introduces a non-normative and freely implementable transfer functionality using attestations and revocations.

But that's a lot to unpack, so we'll do it separately in the following sections.

As the probability of a key's leak increases over time, preventative key rotation is an established industry best practice. Users following such practice hence retire old keys for newly created ones to minimize their exposure to attacks. A common concern about account-bound tokens is that they directly bind assets to a user's account (and hence their private key).

The argument is that when assets are inseparably-bound to an account, a user is discouraged from rotating their keys frequently as it'd require a lot of effort to revoke and re-assign their property to a new account.

And while this argument can easily be made theoretically, in practice, we'd like to argue that it has to be made on a case-to-case basis.

For example, in the case of a smart contract binding an account-bound property to a person's wallet, we'd assume the contract giving the person the possibility to reassign their property under special conditions.

Indeed, depending on the university's ABT revocation and re-assignment process, that'd discourage (very tedious process) or encourage (very lightweight) key rotation.

To encourage preventative key rotation best practices, we think ABT issuers should carefully design their re-assignment processes. We believe that users of such services will eventually flock to those that implement the most fitting models. But we don't believe there to be a one-size-fits-all solution.

Secondly, it's worth highlighting what happens to Account-bound tokens in the

case of a private key leaking e.g. publicly. Assuming the key-possessing

attacker can front-run any on-chain interaction, e.g., they could call

EIP-4973's function burn(uint256 _tokenId) to non-consensually revoke the user's credentials. However, contrary

to e.g. ERC20 or ERC721 tokens, an attacker wouldn't necessarily be able to

steal an account's property as there's no permissionless transfer function

exposed.

But again, it depends on the specifics. If, e.g., ABTs are used by an undercollateralized loan platform to determine the user's credit worthiness, then yes, the attacker may be able to take out a loan under false premises.

However, having ABT-issuing institutions control the revocation and re-assignment process may be beneficiary in case of leaked keys too.

A university, being asked to re-assign ABTs to a new account, may ask the student for identity verification (e.g. a video call). So while an attacker may still be able to front-run all of the user's on-chain interactions, depending on the ABT-issuer's re-assignment process, they're not capable of passing their identification process's threshold.

Finally, in a high-trust environment, e.g., when Account-bound tokens are used to represent the owners of a Gnosis Safe, in case of a private key leak, the clumsy user can talk to their peers off-channel to announce key leakage and hence initiate the social account replacement procedure of the multi-signature wallet.

Finally, it's important to mention here: A consensus around account-binding of tokens can enable a complete re-thinking of the significance of accounts. It may just enable the opposite of what Verifiable Credentials proponents often use as the argument against Soulbound tokens: It could make Ethereum EOA accounts irrelevant.

Consider this: A Gnosis Safe multi-signature wallet that requires two-thirds (2/3) of their owners for any on-chain interaction makes the leakage of a single key less risky in terms of losing assets than if those were stored on one person's EOA account.

It's because the Gnosis Safe is still fully functional with one compromised key, assuming the non-compromised owners can safely communicate about the next steps: revoking the publicly leaked key.

The goal of EIP-4973 is to generalize the permissions/policies a Gnosis Safe is currently "issuing" to owners into a canonical interface supported by an on-chain primitive that is parsable by wallets and indexers.

So rather than discouraging frequent key rotation: EIP-4973 represents a reasonable shot at getting rid of the messy leakiness of accounts and key management by allowing technical innovation in the space of private and high-trust crypto dapps like the Gnosis Safe or the MolochDAO.

Yes, you're reading this correctly. We're not going to claim anything utopic here. While the scope of an Ethereum Improvement Proposal is far-reaching and powerful, it's not magic, and it cannot prevent the myriad possibilities of misuse. Similarly, e.g., IEEE RFC authors can hardly prevent others from being mean or straight up abusive using email or HTTPS.

But let us be clear: None of Ethereum's infrastructure or standards currently prevent misuse. If you want to dox someone's Ethereum account, there are already many ways to do so. And controversially, there is not a single way to delete that data. But, this is a discussion entirely out of scope for defining a token standard interface for wallet implementers within the EIP process.

However, we do think it's necessary to evaluate our actions against the ten principles of Self-Sovereign Identity [1, 2].

EIP-4973 implements a function burn(uint256 _tokenId) and requires it to be callable at any time by an ABT

owner to ensure their right to publicly disassociate (or in MolochDAO terms:

"ragequit") themselves from what has been issued towards their account.

However, we also want to be conscious that consent in a constellation between

more than two individuals may become more complex than always prioritizing a

single person's will. Paper contracts between e.g. three persons exist where

one person's consent withholding can block decision-making of the two other

persons. So while it looks like the function burn enables consensual

interaction, that may only be true for a constellation of two persons - not

more.

Similarly, we, the EIP-4973 authors,

are aware of the problems that non-consensual minting can create. But using a

variant of EIP-712 structured data

hashing and signing, we believe an optionally-implementable function mintWithPermit can be implemented to allow an ABT receiver to

"lazy-mint" with an ABT

issuer's signed permission. Particularly one of us, Raphael, with Violet's

ERC1238Approval

extension,

has been looking into this technical possibility.

We'll update this post in the future to reflect our progress.

Yes, blockchains store data practically forever (but consider EIP-4444). And there have been numerous amazing philosophical takes on the subject matter too. The best, in our opinion, is Ribbonfarm's "Blockchain's never forget" article, which accepts blockchain's "dystopian" property of immutable, permanent data availability as a chance to rethink inter-human interaction.

Blockchains like Ethereum currently violate the EU's right to be forgotten. If user data is stored on Ethereum by dapps, it may also violate the GDPR laws in many cases. There is a debate about the alegality of blockchains. And similarly, we think there's acceptance needed towards understanding blockchain as so culturally diverse and international/global that, e.g., the EU or US's local laws won't "just" cut it.

It is not to say that we shouldn't use those laws as guiding principles for implementing technology. But, clearly, in the case of bringing up the abuse potential of ABTs, the community should understand that any other token standard or any other Ethereum transaction can also contain abusive information linking to accounts. It's a problem with Ethereum, not within specific standards.

So generally, we want to encourage more discussion around the topic: But we also want to be clear: This isn't a problem limited to ABTs. It is a problem of blockchains and should hence also be discussed on that level.

ABTs can be misused, and we must work on heuristics to maximally prevent misuse. Within blockchains and generally for any modern and inter(net)-national peer2peer protocol.

Then, once someone understands that ABTs can be re-issued using a sequential revocation and re-attestation, an accusation that has been brought up is that ABTs are vulnerable to censorship, namely because the implementer is in the position to control the re-issuance.

And while, of course, this argument can be easily made, e.g., in the above case of a smart contract issuing an ownership deed to a person, what is vital to understand is that the EIP-4973 account-bound token standard makes no normative statement about the conceptual structure of an ABT minter or how they should be implemented.

A naive implementation of a university using EIP-4973 tokens may indeed be vulnerable to "censorship." But that's because it's implemented fragilely and would require alleging bad intent. It also touches upon the question: What equates to "censorship" and what equates to "moderation"?

But we, the authors, are discordant on how to deal with structural censorship. Some of us take the stance that technology must prevent harm. That's the mainstream tech opinion where for example, social networks interfere actively. While others of us say that immutable blockchain-documented misbehavior is ultimately a good thing for accountability and not technology must prevent harm but the respective legitimate jurisdictional system of a user.

The censorship-vulnerability argument against ABTs is one that assumes a worst-case scenario of mal-intended implementers. But the EIP-4973's document now even makes a normative statement as a means to prevent mal-intended censorship:

We recommend implementing strictly decentralized, permissionless and censorship-resistant re-issuance processes.

For making a visual example, let's imagine that a future metaverse land title may not be emitted from a single person in control and power (read: "Censorship capability") but rather from an anarchist or democratically-organized smart contract many people can coordinate with.

ABTs do not mandate a token issuer to be a centrally controlled and censorship-vulnerable entity, and so the argument that ABTs are censorship-vulnerable likely stems from being misinformed.

We should implement ABTs issuers in a decentralized fashion. We should properly rethink how our trust-crediting institutions work. We should fit them into the mold of the interfaces we have available. And if they don't fit: Let's change or add new interfaces.

In her post "Soulbound Tokens (SBTs) Should Be Signed Claims", Kate Sills makes the argument for why Soulbound tokens are better to be stored off-chain as signed credentials.

By properly defining "signed claims", the post makes an important contribution to also narrow-down Account-bound tokens: Namely because we're now acknowledging the coincidence of EIP-4973 tokens being useful to issue on-chain credentials and at the same time, because we've now become conscious of having to further distill our ABT definition to distinguish ourselves.

Our goal is to create special ownership deeds or permission primitives; not off-chain claims or credentials.

Sills' definition of a claim is useful:

A claim is a statement that someone makes about themselves or someone else, which may or may not be true.

and that:

An essential part of evaluating a claim is evaluating who made the claim, their expertise, their experiences, and their motivations. The process of evaluating a claim is very subjective and context-dependent.

Now, Sills' outlines why statements complying to the definitions above make no sense to be stored on-chain - we agree with her, especially when evaluated through the ten principles of self-soverein identity. The following is an attempt and failure at complying to those principles by pretending to store signed claims on-chain:

So, hence, since ABTs shouldn't be used as credentials on-chain: what should they be used for?

Originally, one of us submitted EIP-4973 as a solution for implementing Harberger property when it became apparent that "Non-Skeuomorphic Harberger Properties may not be implementable as ERC721 NFTs".

The problems that lead to this approach are that EIP-721 and other token standards implicitly assume the ownership structures adhering to normative private property laws. Even before Weyl et al's "Decentralized Society" paper, we had blogged about it and so the work on EIP-4973 goes back to specific Solidity implementations of Harberger property contracts [1 2] in Ethereum and the Partial Common Ownership working group.

Direct motivating factors for publishing

EIP-4973 was that it would allow

users to display an NFT-ish token in their wallet while giving wallet

implementers the possibility to call

EIP-165's supportsInterface method

for feature detection. In that sense, Account-bound tokens were meant as a

simple backward-compatibility hack "free-riding" on any wallet implementing

EIP-721.

So, strictly speaking, although we acknowledge the EIP-4973 standard to coincidentially be useful for issuing credentials, it must be noted that our focus is on creating new type of ownership experience.

Finally, we acknowledge that there are cases where it can make sense to put credentials or claims on-chain. In a post titled "Where to use a blockchain in non-financial applications?", Vitalik Buterin makes the case why storing some credentials on-chain seems useful.

Finally, a word on how we see Soulbound tokens being standardized.

Already within the working groups for EIP-4973, we've branched off and listened to the community's feedback that is interested in, e.g., binding tokens to ENS names. As a result, we've "forked" EIP-4973 to a new standard called "name-bound" tokens and submitted it as a draft PR to the ethereum/EIP repository.

Additionally, by intentionally binding tokens to accounts, we've furthered the discussion around whether that's a good idea. As a response, more generalized approaches like Micah Zoltu's EIP-5114 are now being submitted too. It allows to bind ERC721s to ERC721s and hence doesn't have the supposed key rotation issue.

We hope EIP-5107, EIP-5114 and EIP-1238 aren't the last attempts at defining Soulbound tokens for Ethereum. Rather, we think that for collective intelligence to emerge, although it often feels personal, many new ways of expressing property on-chain will be discovered to understand what users truly want.

We must encourage other standards. Let's learn from each other to create a decentralized society and find web3's soul.

published 2022-05-30 by timdaub